From Britain to beyond: The spiritual journey across the world of Dr. Graham Dwyer (aka Gangaram)

It’s often foretold that exploring the world is how we capture the magic and essence of life.

In this feature for Travel News Blitz, journalist Disha S. Charan seeks insights from Dr. Graham Dwyer, Oxford scholar of anthropology turned Spiritual Guru and a seasoned traveller across continents.

They say the world is the greatest classroom, and nobody knows this better than Dr. Dwyer.

He has explored countless countries and has immersed himself deeply within diverse traditions across various enriching cultures worldwide.

What began as a curiosity turned into a lifelong connection with spiritual teachings and the meaningful lessons they hold.

He is also a renowned author of several notable works such as The Divine and the Demonic: Supernatural Affliction and Its Treatment in North India, The Hare Krishna Movement: Forty Years of Chant and Change, and more.

From giving lectures in Oxford to directing documentary films, from meditating with spiritual monks to supporting underprivileged rural children in India through education, his philosophy is not rooted in rituals or sacred pilgrimages but about returning inward, to the self.

Meditation, he insists, is a universal practice that cuts across religion and provides a path to balance and peace which stands as an antidote to the anxieties of modern life, which is perfect for an online generation that is often stressed about the materialistic expectations they uphold.

Dr. Dwyer’s path blends adventure, wisdom, and timeless lessons for a generation still searching for their purpose and place in this world.

His advice? Travel with intent, not conquest.

When someone asks “What do you do?” - how do you introduce yourself? Could you take us back to the very beginning of your journey?

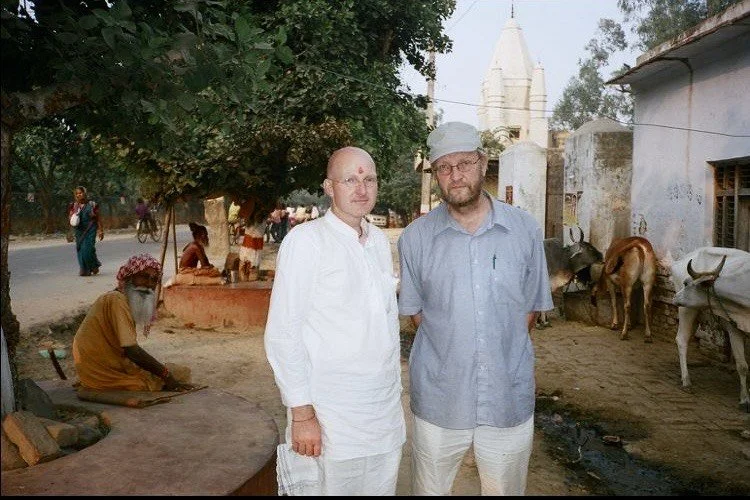

GD - When someone asks me “What do you do?” I always mention my passion for visiting India, and that also takes me back more than half my life to when I first visited South Asia to begin my Oxford University doctoral research in Rajasthan. It was when I was 31 years old.

I made a study at that time of a famous Hindu temple in Rajasthan, a study that was later published by Routledge in 2003: “The Divine and the Demonic: Supernatural Affliction and its Treatment in North India.”

It was a study of spirit possession and curing ceremonies carried out at that Hindu shrine, as well as being the beginning of my successive research and publications about India and Indian religious traditions, including teaching and lecturing.

So, that is how I often introduce myself.

If someone asks about me or my work in particular, somehow or other the word “India” always surfaces in that kind of conversation.

But to go back earlier, say to my 20s, when I was beginning to plan possible pathways my life might take, I started to travel quite a bit, visiting in due course various countries nearer to home in England.

I went to many European countries, and also to north Africa, as well as to sub-Saharan Africa.

I got a sort of travel bug, although it was not essentially about ticking off a list of countries to visit. Far from it.

I always actually find it a bit irritating when, for example, I hear the expression: “I’ve done country X; next year I’m doing country Y.”

For me, that’s often just like something one is trying to show off about or to impress friends about. It reflects a sort of ugly culture of consumption, I think, like ticking off a list of haute cuisine one has partaken of or famous restaurants one has frequented.

In my case, I really wanted to understand people and culture and indeed the whole of humanity, or at least get some perspective on all of that.

That’s why in my post-graduate days – my first degree was religious studies – I began to focus on social and cultural anthropology.

I was originally planning to do a D.Phil. on traditional religion in Africa as an anthropological project.

But when I did my Master’s degree in anthropology at Oxford, I was introduced to so many ethnographic studies in various different regions of the world and at the time read more and more about India.

I got hooked on that. And ever since then I’ve been travelling to India every year – sometimes even going there twice a year – to do research or to meet friends and, at least over the last decade, to do charity work too.

How does one go from Oxford, UK, to being known in India as Gangaram, a Brit who speaks Hindi and a spiritual teacher? What led you down this path?

GD - My first name Graham, strangely perhaps, was not always easy to pronounce for many of my friends and contacts in India; so, one day one great Jain Swami, a spiritual teacher and close friend, said that I should be called Gangaram. That stuck and became my name there.

I also liked it very much anyway, a name that is a delightful compound: Ganga (the sacred Ganges river) and Ram (or Rama, a deity worshipped by Hindus everywhere).

When I meet new people in India and introduce myself it is always first as Gangaram, and people on my trips always both like and truly appreciate that.

I equally try to speak Hindi as often as I can when I’m in India, as well as going by the name of Gangaram, which is also much appreciated on my trips.

I learned Hindi and the Hindi script (Devanagari) when I was a student in Oxford, as I needed that to do my D. Phil. research.

And that’s one thing generally I consider important for anyone to practice when journeying abroad in different countries with different languages used.

Everyone should try to do this. It means a true show of respect to them, I feel; and because language is invariably part and parcel of culture, it means respecting that too.

The culture of India, despite all the land’s amazing relatively new modernisation and growing international importance in the world, is still very much a spiritual one.

That has always been a great attraction to me.

I’ve been greatly inspired by India’s religious outlook and practices, which take a variety of multifarious, joyful, and tolerant forms.

I was personally drawn to what I consider the heart of Indian religious life, namely its inherent tolerance for all religious traditions and ways of experiencing spirituality.

But I have been particularly close to Jainism, the main teaching of which is non-violence; and it’s also why I prefer vegetarian food and like their teaching about avoiding animal cruelty.

Anyway, when I was doing my early research in India, I was introduced to Terapanth Jain monks and their leaders called acharyas. I learned meditation techniques from them, which I continue to practice today as well as teach to others.

Because of my close connection with them, I was requested by the acharyas more than 30 years ago to bring two Jain monks to Oxford University to give lectures.

I did that and organised with other friends in the UK a lecture programme for them at the University of London as well.

These were very exciting times, not least because they were the first Terapanth Jain monks to come out of India with the authority of their acharyas in their entire history.

It was a momentous event and a personal delight to facilitate it all.

These monks are still very close friends now, and with one of them I currently do a great deal of charity work in India, involving creating scholarships for clever students from underprivileged homes, providing food kits and medical support for widows and for poor families, and much more besides.

This is very fulfilling for me, not least because it enables me to give back something to India, as India, I feel, has always been giving to me in so many ways, especially in respect of its spiritual culture and because of all the friendships I have made there.

MORE FROM DISHA S. CHARAN: F1 news: Freelance data engineer and technical coordinator Nida Anis on breaking barriers and women in Motorsport

You’ve authored many spiritually influential books. Could you tell us more about the Hare Krishna movement and why it has been central to your work?

GD - Well, I have written or co-authored eight books in total, as well as many scholarly articles in peer-reviewed journals, mostly dealing with Indian religious traditions.

After my doctoral research in Oxford, which took me to India in the first place, I was looking to do post-doctoral work in the UK where I live with my family.

Also, because of my interests in India I wanted to find an Indian religious community more or less on my doorstep, and Hare Krishna was what first came to mind, not least because there are so many Hare Krishna temples here.

So, I went to the Hare Krishna movement’s headquarters in the UK, which is not far from my London home. It’s near Watford and is called Bhaktivedanta Manor, a very large shrine set in many acres of beautiful green land and gifted to the Hare Krishna movement’s Indian founder by George Harrison of Beatles fame.

It’s quite an amazing temple and attracts large numbers of devotees and followers, literally tens of thousands every year.

As soon as I went there, I was introduced straight away to Radha Mohan Das, the temple’s communications secretary. Radha, a Hare Krishna monk at the time, was very friendly and helpful and, importantly for me, provided access to all parts of the temple, as well as supplying all the information I needed to get started on research there.

Soon after initial meetings with him, we entered into a very fruitful research collaboration. This was especially exciting because it meant that we could work together, he as an insider informant, with me as an outsider-scholar.

This led to two highly acclaimed book publications, one in 2007 (titled “The Hare Krishna Movement: Forty Years of Chant and Change” and one in 2012 (titled “Hare Krishna in the Modern World”).

These books, which were very well received from the beginning, not only by academics and students, but by many general readers interested to learn about Krishna Consciousness, have become increasingly popular.

And I truly have enjoyed all my experience in connection with the Hare Krishna community, the vast majority of whose followers I have always found to be truly spiritual and deeply devoted to their religious calling, as well as kind and welcoming.

Your film Leap: A Documentary Film about Faith, produced with Dr. Jouko Aaltonen, explores the guru–shishya relationship (teacher-student relationship). What inspired you to explore this dynamic, and what experiences led you to it?

GD - My work as researcher, scriptwriter and assistant director on the documentary film “Leap” was inspired in part, of course, by my earlier research on, and writings about, Krishna Consciousness.

But also, as the movement is a very colourful and exotic Indian religious tradition – and one, I should add, that has firmly transplanted itself on to Western soil where it has both put down strong roots and continues to flourish – this was another key reason.

The ritual practices and devotional activities of its followers, with their traditional Indian religious dress, as well as the fascinating ceremonies and festivals devotees hold, I felt all naturally lend themselves to film.

Also, I was interested to explore why devotees search within their movement for gurus and what it is that the gurus themselves offer that is so attractive to devotees.

All of this reflection led me to forge a successful professional relationship with award-winning documentary film maker Dr Jouko Aaltonen, whose prestigious film company Illume Oy is based in Helsinki, Finland.

We became good friends and enjoyed an amazing partnership, one that involved filming for two years members of the Hare Krishna movement and its leaders in London, Helsinki and in the movement’s homeland of India.

Most of the filming in fact was carried out in places sacred to Lord Krishna in India, and we were extremely fortunate to receive full cooperation and support from one of the most influential gurus in the Krishna Consciousness movement.

That guru is H.H. Radhanath Swami who has thousands of followers worldwide and who equally is an increasingly popular figure outside the movement in the New Age community, including also many interfaith groups.

A Finnish close disciple of his called Keshava Madhava Das also agreed to take part in “Leap,” which was extremely fortuitous for us, as he is a deeply committed Hare Krishna priest.

The film we made documents the stories of these two powerful characters: Keshava, a tram driver in Helsinki, and his guru, the movement’s foremost charismatic spiritual leader based in Mumbai, India.

Keshava started out in life as Kenneth, a lonely boy who witnessed his grandfather’s death, which had a profound effect on him and brought him into the orbit of Krishna Consciousness.

His guru, H.H. Radhanath Swami, was originally Richie, an American small-town boy, who is now revered within the movement as a living saint.

Importantly, “Leap” offers unprecedented access into their relationship and into the wider Indian guru-disciple system, as well as the spiritual concerns of each of these intriguing characters.

In the film, I believe, we truly gain remarkable insight into the ancient Indian guru-disciple relationship, as well as a penetrating perspective on one of the world’s most fascinating religious traditions.

The success of the film ultimately is a testament to its absorbing quality and freshness and why it has had many screenings, including television screenings in Finland.

It was a true delight to work on it and one I consider to be a great personal achievement.

“Leap: A Documentary Film About Faith” has since been made available by the film company Illume Oy on YouTube, and the whole film can now be fully watched free of advertisements by anyone who might wish to view it.

You recently travelled to China. What sparked your interest in that journey, and what insights did it bring you?

GD - My recent China visit was with my wife, Dr. Bridget Heelan, and it was very eventful and interesting.

I had previously never really considered going there as such. It was my wife’s idea and had her stamp on it from the beginning.

But I was actually surprised when I got there, as I had thought that, being a closed, totalitarian society, it would not feel free at all and that we would even perhaps be followed by official minders wherever we sojourned, as happened to me in the mid-1980s when I visited Moscow and St. Petersburg in what was then the USSR or Soviet Union.

I was wrong about all these imaginings.

We went to a number of cities, starting with the capital Beijing. But one of the highlights of the trip was Xi’an, where the 2,200 years old Terracotta Warriors were found as recently as 1974 by a farmer digging a well in his field.

We visited many ancient Buddhist temples and pagodas as well, in part because of my interest in religion.

What was really striking about those trips is that we observed lay Buddhists being free to worship at the shrines.

Informal discussions with worshippers also confirmed that there were no restrictions on it, and that they could come and go and express their devotions with impunity.

Discussions I had with some Buddhists, however, made it clear to me that religion was still officially discouraged, and I was told that one could not be a member of the Chinese Communist Party, for example, and an avowed religious practitioner.

At least that was said to be the official line. But there were apparent ways around this, or it could just be overlooked, it seems.

Interestingly, one informant told me that her own father was a sincere devotee of Buddhism and a Chinese Communist Party official.

This was in the world-famous tea plantations of Longjing, where my wife and I visited one day both to see the amazing plantations and to sample and buy green tea.

When I asked the woman how that was possible, she stated that her father never made his religious affiliation known to others publicly, although his family members and friends all knew about it; and it was, therefore, no secret.

So, I didn’t really find or detect any obvious major crackdown on religious expression or religious worship in China. That was a great finding as well as a relief.

All the Chinese cities and regions we went to had amazing infrastructure. I was surprised by that too.

I had not expected Chinese cities to be so advanced, and it made me reflect that the infrastructure there was even superior to my own city of London.

Trains also were incredibly efficient. We took bullet trains everywhere, trains that achieve speeds of 217 miles an hour. Quite phenomenal. As passengers we felt that we were hardly moving from the comfort of our seats.

And the bullet trains everywhere departed precisely at the scheduled times, even to the second. The journeys by bullet trains were sensational. I would definitely recommend a trip to China to anyone thinking about going there.

Some might say your journey to enlightenment feels almost like something out of fiction - echoing The Monk Who Sold His Ferrari. How do you see your travels as guiding others into meditation, reflection, and spiritual practice?

GD - I would never say that I was enlightened. I’m not. Not at all. But I’ve experienced positive life-changing events, especially due to meditational practice.

I’m a big fan of it for many reasons, spiritual as well as in terms of more practical matters, like managing emotions, trying to live a happy and contented life, and with peace of mind.

All of this has always been important and is perhaps even more so today, as we hear so often about mental health problems from which so many people suffer, both young and old alike.

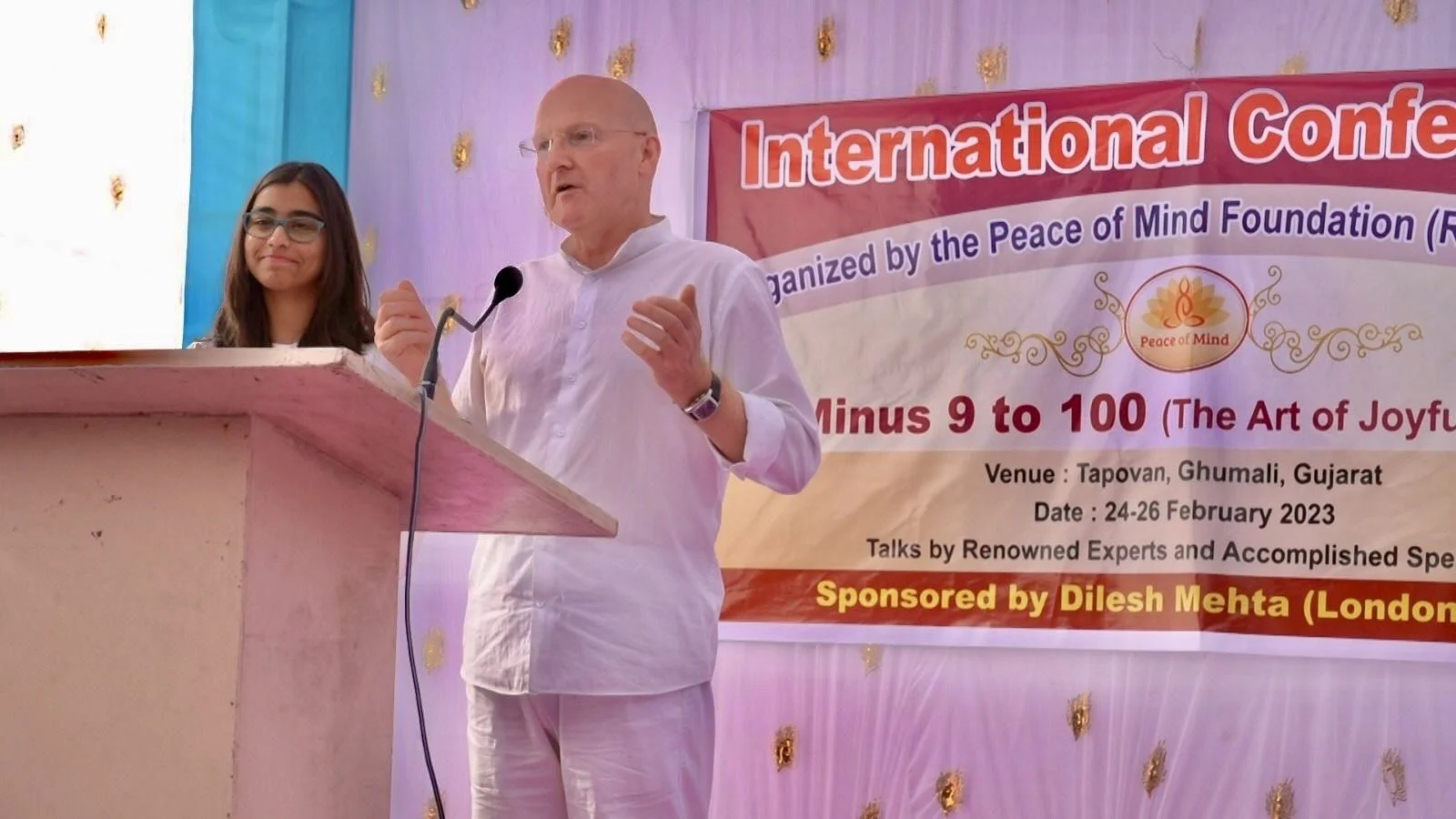

One thing about doing meditation is that it is non-sectarian. One can be a practitioner of any faith (or no faith at all) and still get tremendous benefit from it. And that is why I promote it, as well as teach others how to do it.

Because I’m a fan of meditation and know that it can truly help people with their quality of life and bring mental peace.

I have written a book about it in collaboration with one Jain monk, with one of the very same two Jain monks I brought to Oxford and London universities as far back as 1992 to give lectures.

As mentioned earlier, that was when I was doing my D.Phil. The book I wrote with that Jain monk is called “Living Meditation,” and it explores different techniques without any kind of religious affiliation being advocated.

It discusses different steps and ways of practising meditation, and it is helpful for those who are just starting out doing meditation, as well as being equally beneficial for advanced practitioners.

Anyway, in terms of spirituality the practice of meditation is immensely powerful. The root of the word spiritual, of course, is spirit (from Latin “spiritus,” meaning “breathing”).

As is well known, perhaps, many techniques of meditation often involve attention to the breath, but it is also something that is at once a natural process and one that the witnessing of (or the concentrated observation of) brings the practitioner back to him or herself on the spiritual journey.

This is important, I believe, as any true form of spirituality must be able to effect it.

Meditation does this, enabling the one who practices it seriously to achieve self-realisation.

That, for me, is the heart of genuine spirituality.

Indeed, one great Indian sage called Sri Ramana Maharshi once said that a spiritual seeker can travel the whole world around in search of salvation or enlightenment but in the end has to come back to him or herself if this is to be achieved.

So, it’s not a matter of simply doing rituals or travelling to far flung locations in search of great gurus or sacred sites. Not at all.

For one ultimately has to come back to oneself, which is the key point, and meditation, in my view, is supremely placed for this.

You’ve collaborated with Jain monks, nuns, and spiritual teachers. What have these encounters taught you about simplicity, discipline, and inner peace?

GD - I have collaborated with many Jain monks and nuns on various projects over the past 30 plus years, and I have learned many important lessons from them.

Most of my encounters with spiritual teachers who have had an impact on me have also tended to be Jains.

Regarding inner peace, I think I have dealt with that topic essentially in my earlier comments about meditation.

I actually learned most of what I know and practice from them. In part that is perhaps because the previous spiritual leader of the Terapanth Jains, Acharya Mahapragya, whom I both met and knew well, developed his own system of meditation called PrekshaDhyan.

Learning how to do Preksha has been beneficial to me, but I have also experimented with other systems too.

Other lessons I have learned from Jain monks and nuns, as well as from one Jain Swami called Dharmananda, who was like a father to me, are connected with things like dealing with expectations.

I could say a little about that in answer to the question you have asked me to address.

We all find ourselves at some time or other frustrated by thwarted expectations.

Many people in fact are often continuously plagued in this way and suffer a great deal as a consequence.

Expectations can create an enormous amount of unnecessary mental pain and self-inflicted torture.

The whole of human experience is awash with expectations of all kinds: when we go to university, we expect to get the grades we worked for; when we get a job, after putting in a great amount of time and effort we expect promotion or an increase in salary; if we have a partner or get married, we expect so much from that relationship; and so on and so forth.

But just think for one minute: if you had no expectations at all – no expectations whatsoever – in any of these or in any other scenario or situation imaginable, would you have removed a huge chunk of unnecessary suffering from your life?

I think that if anyone considers this kind of question deeply, they would have to agree that the answer to the question would be an undisputed “Yes.”

Yes, undoubtedly, an enormous burden of suffering would certainly be avoided here.

I’m not saying that we can be completely free from expectations, although all thwarted expectations create pain and misery.

However, we can and should try to be less dominated by them and be aware of them whenever they arise in our thoughts so as to reduce or control them.

This is an important simple yet profound lesson I have learned from certain monks and nuns whilst travelling in India.

It is also a lesson I try to put into practice in my daily life and one that has helped me tremendously.

All of this requires discipline, of course. It is a mental discipline that is needed.

We need to be diligent mentally in order to spot expectations when they arise in us and try to avoid building things up in our minds to avoid crippling disappointment and self-inflicted mental torture.

It means also cultivating in ourselves a balanced way of living, a way to live that is tolerant and patient and equanimous, calm and peaceful. And it all goes hand-in-hand with the practice of meditation about which I have already spoken.

Many Gen-Z today are searching for meaning in a fast-paced, chronically-online globalized world. Based on your journey across cultures and traditions, what advice would you give them?

GD - Members of Gen-Z indeed are forever online, it seems, especially for purposes of social media (of which they are both avaricious contributors and consumers).

A lot of it causes them so much mental anguish and pain, as well as joy and excitement.

It’s like a pendulum swing from torture on one side to elation on the other. And that’s so damaging to any kind of balanced lifestyle worth having.

It can also and perhaps is like a drug for many young people in that generation, as it can also similarly be so for many other groups who might be older.

Searching for meaning is obviously a big part of all of that, searching for identity and a sense of purpose, for example, and so much more besides on life’s journey.

As one who has travelled a great deal myself, I would certainly recommend travelling to members of Gen-Z.

I don’t mean that this should just be another way of showing off to one’s online followers, posting online that one has visited country X this year and planning to go to country Y the year after that, etc.

But travelling really does open up the mind and is a great way to gain personal insight and meaning, as well as a means of learning about other cultures and societies.

It can and should provide a path to great self-discovery and the wider world, as well as bring new perspectives on life.

There is that old saying, namely, that travel broadens the mind. I’m a big believer in that.

What I have so far said in a way would perhaps be just general advice to Gen-Z. Choosing where to go, however, would be more a matter of specifics for them.

Essentially, it’s important for members of that generation (like members of any generation perhaps), I believe, to find out what they are interested in and what their personal talents might be.

In my own case, it was to do with religion and quietist traditions of spirituality, both of which I have been fortunate enough to make a number of contributions.

It was that interest that took me to other countries and cultures, India in particular, as I have already discussed, and a journey that helped me find my own sense of purpose in life.

Without question, looking to one’s own personal interests and talents is key when it comes to places to travel to or to explore.

That cannot be prescribed in any direct manner by me or by anyone else and would undoubtedly have to come from each and every individual when planning possible places or peoples to understand.

But to be clear, I am an advocate of any kind of travel, not least because it opens one’s eyes to other ways of seeing the world, to other ways of behaving, and to other ways of creating meaning.

So, with Gen-Z I would very much want to encourage them to go on such a voyage of self-and-world discovery through travel.

From this they can certainly gain enormous benefit, one which will aid them as they steer their way through and negotiate the steps of their young lives.

Gen-Z are the new future, in fact the future of the world.

Its members, in my view, should as far as they can learn about and embrace other peoples and cultures, not merely via an online screen, but in the delightful exchange of meeting them in exciting face-to-face travel possibilities.

That would be my advice for them to consider.

You’ve often referred to India as your second home. What was the first moment you truly felt that way, and what are some of your most memorable experiences here?

GD - I have, for sure, often said that India is my second home.

I’ve also sometimes said that England is my second home, India being the first of the two! That’s because I truly feel at home in India.

I love the culture, the people, the spirituality charged atmosphere, as well as the cuisine.

Vegetarian food in India is so incredibly varied and delicious. There’s really no match for it, such amazing variety is to be found there.

But there are and have been many experiences – far too many to enumerate here – that make me feel India is home.

Strangely, in a sense, the first time was soon after I arrived there way back in 1990.

I was 31 years old then. Someone somewhere was cooking daal, which is actually my favourite food. That smell made me feel in an odd sort of way that I had always been there or had always lived in the country (or perhaps had even been there in a past life – as some of my Indian friends try to assure me is the case).

Whatever it was in the end, the smell of the cooking pulses – the daal – had an almost indescribable effect on me.

But equally what stands out about my very first visit to India is my arrival there by aeroplane.

I was seated on the plane next to an Indian passenger who talked with me from time to time on the journey and who asked about the reason why I was travelling.

Anyway, before the flight finally landed at Indira Gandhi International Airport in Delhi, that same Indian passenger asked where I was going to stay.

I hadn’t booked any hotel and was planning simply to find one when I got out of the airport.

Without a single hesitation he invited me straight away to stay with his family, at least overnight or until I had found a suitable hotel.

I took up his offer and stayed with that family that first night, and all his family members, including the Indian man who had invited me, made me feel extremely welcome, as well as prepared wonderful food for me.

It’s an event I’ve never forgotten and one which I always feel truly grateful for.

I’ve met so many families like that almost anywhere and everywhere I’ve travelled in India, and that means the whole length and breadth of the sub-continent.

Over the years and partly because of my research in India I have made very many friends there.

It truly is a home for me and no doubt always will be.